Driven by a Perennial Need to be Fooled

Are we driven by a need to be fooled? A look at the intrinsic need among people to believe in the make-belief.

Over the years, one question repeatedly pops up in my mind: “Do we have a perennial need to be fooled?” In many instances this is linked to the world of make-belief that attracts us so much, be it the illusionary world of cinema, theatre, or magic.

Yet in many other instances, this has everything to do with our innate need to believe in all things paranormal, and the inexplicable urge to be ‘fooled’ by extraordinary claims. Is this unique to India, owing to our cultural roots, or is this a global phenomenon, is a thought worth pondering upon.

This thought found its roots a couple of years back as I watched a rather unique interaction on television, where a group of gurus and godmen individually took potshots at the philosophy of another of their brethren. The topic of discussion then was a Nirmal Baba, who had burst on the scene and had quickly amassed a following of millions of people.

The aspect that made Nirmal Baba unique–and hilariously funny to some–was the bizarre answers, advice, and solutions he gave to his followers. A devotee suffering from a financial crisis in business was asked “when was the last time you ate pani puri,” and informed that eating some would remedy the situation.

Even the greatest proponents of the powers of placebo would be taken by surprise by Nirmal Baba’s suggestion to another devotee to buy better (branded, more expensive) footwear to remedy his personal situation.

It was interesting to note that while the various godmen spared no effort to ridicule Nirmal Baba, they were careful to protect their own terrain, and use the opportunity to project their own philosophy as “the real one”.

So what is it that makes us believe and act on the most ludicrous of claims, without asking for any semblance of proof? Is our need to believe so strong that it has overpowered all our critical faculties?

A few months later, we saw yoga guru Sri Sri Ravishankar being invited to present an inspirational talk to the students of IIT Kanpur. After having expounded on the philosophies and advantages of yoga, this most celebrated swami decided the time was ripe to do “a special demonstration” for the benefit of the audience.

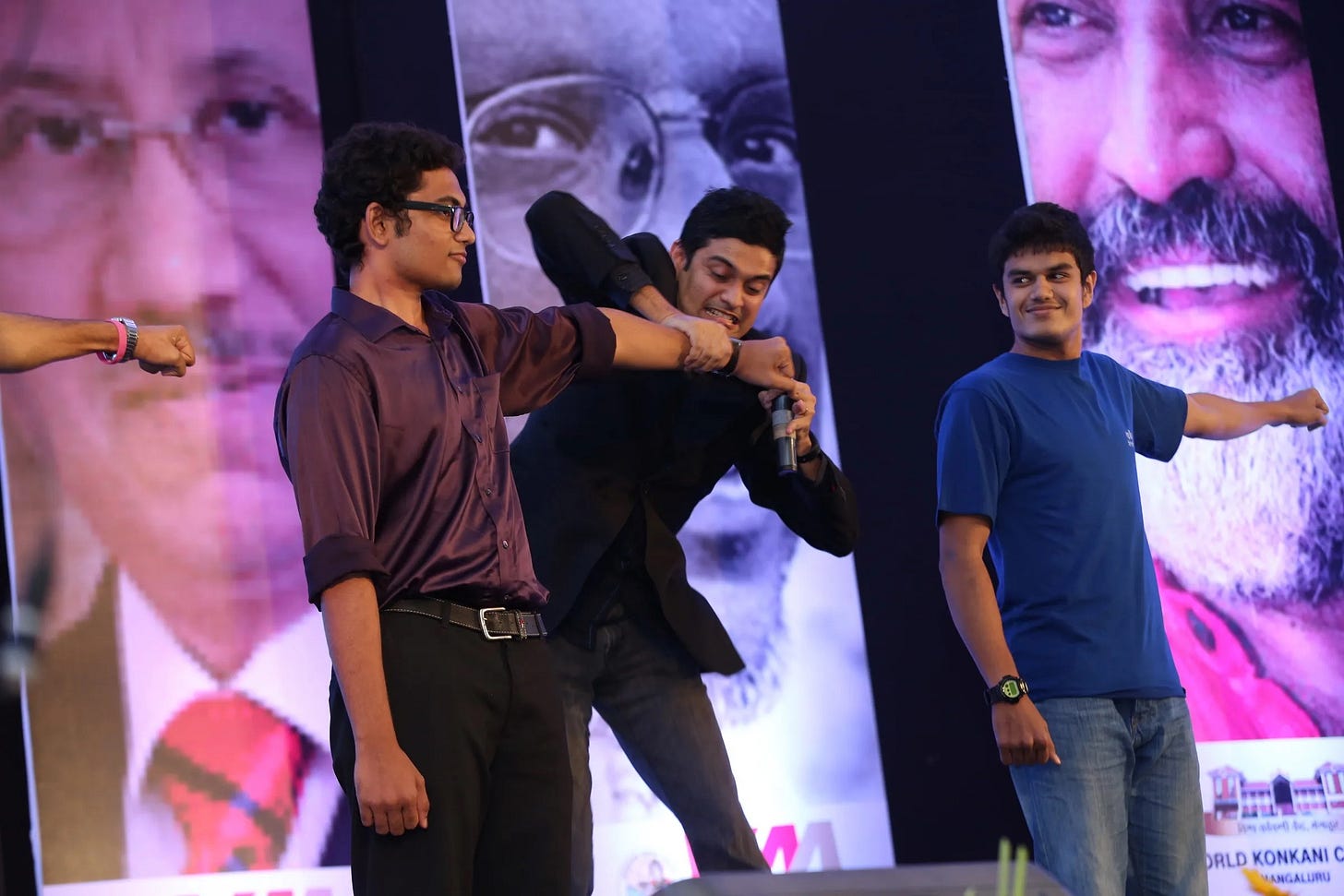

Having called a student volunteer on stage, the swami asked him to extend his right hand and hold it taut. Exerting sizeable pressure with his hands, the swami pushed the hand down, overpowering the student with ease. Playing the part of an excited scientist to the hilt, the swami brought out a small vial out of his pockets, and dropped one drop of the mysterious liquid on to the student’s hand.

The result: the student seemingly had a surge of energy and strength, and now no amount of pressure exerted by the swami would push his hand down! Why the swami had to indulge in this particular act that has been used by magicians over hundreds of years is anybody’s guess.

The thunderous applause by the audience was mellowed down only a wee bit, when another student walked up on stage and challenged the swami that he would like to try the same. He meant he wished to play the part of the swami and examine if the unbelievable claims could really stand up to his test.

And this is important. For here was a student who exhibited critical thinking and scientific reasoning, and said if this demonstration is real, then it has to work in my hands too. And it is this approach that is seen to be increasingly lacking in our general psyche.

More recently, when then Member of Parliament and industrialist, Naveen Jindal launched his latest initiative of the Tiranga bangle, not many blinked at his claims that wearing this “trivortex-treated” copper band healed a variety of ailments, from arthritis to acidity to cancer. And when confronted with evidence that suggested that the claims were a pseudoscientific scam, the MP was quick to brush aside all criticism with a “it has worked for me and so it is real”.

The belief in the “technology” and its promotion by Mr Jindal was so strong that he rubbished all evidence to the contrary with a strong statement of “not by a competent authority”. The fact that the authority turned out to be not only competent but also highly qualified, and serves on the health and food advisory committees of the UN and WHO made no difference to the blind faith imposed in the pseudoscience claims by the well-meaning Mr Jindal.

That is where the problem really lies. In our ardent need of wanting to believe, we hold on to all the thoughts and ideas that support the philosophy and push aside anything that goes against those beliefs. This is when the need to believe is superseded by the need to be fooled take roost.

The trouble is that this need to be fooled is not limited to religion, spirituality, or healing. It abounds in instances all around us, in every type of extraordinary, unsubstantiated claim made by people; and rather unnecessary, as most could be settled amicably by putting them through a scientific test.

Making a tall claim is in anybody’s hands, but proving that the claim is indeed true is not as easy. This is why, any and all extraordinary claims should be put through a standardised scientific experiment. After all, if a set outcome is claimed off a set of actions, then it is natural to expect that the same outcome would occur in a laboratory test too.

Simply put, every claim should and must be substantiated, and the onus of proving the validity of extraordinary claims lies totally with the claimant. Indeed, it is too easy to say eating sand will heal you of stomach ulcers, but quite another to prove that in a scientific study.

This brings us back to the original thought: have we forgotten to think critically and ask the most primary of questions? Why is it that we do not stop to think and ponder, “so what makes this work?” Even more, what stops us from asking the question, “has this claim been tested and by whom?”

A significant field that then calls attention to itself is hypnotism. A highly debated field, hypnotism had its fair share of supporters and detractors. There are those that say it is real, and then there are those who say it is all make-believe. This debate attains significance when we consider that this difference of thought exists among professional hypnotists themselves! And this difference is further accentuated when we understand that these school of thoughts are well developed and defined.

This is the context that makes me question the idea of “past life regression” that is so popular among many “hypno-therapists” and of course, their hapless clients. Yet, if hypnosis as a field itself is so divided, where many practitioners think of it as the hypnotised person playing along to the suggestions of the hypnotist, what makes past life regression any different?

In fact, it makes it much dangerous. The one known fact about hypnosis is that it is the best tool to fully utilise your creativity. As an extension of that, it is logical to consider that the mental journey “into other lives” is nothing more than creativity let loose. The worry is if people, especially the troubled ones, start believing in these “visions” as real and begin leading their lives per these delusions.

As in the context of that one IIT student who stood up to the most famous godman and asked him to prove the claims he made, it is rather difficult to come across people who stand up and ask the claimant to put his money where his mouths is. In fact, the situation is that people readily empty their pockets blindly believing the claims, without ever stopping to critically examine it.

Why else would people send in thousands of rupees upfront in the hope that the MLM scheme will pay them a margin of that money, month on month? How can anybody with a basic control of their mental faculties fall for the financial and other frauds and scams that we read about every other day?

Is it really the urge to believe in the unexpected and in the extraordinary possibility of the occurrence of good, that makes people fall, head first, into every fraud claim and scam that comes their way?

I think not. To me the best answer to this irrational behaviour of people lies in their innate need to be fooled. We want to be fooled and so do not wish to ask any difficult questions that will spoil the illusion for us. We want to believe in the hope that our strong belief makes the impossible possible.

In recent times, there has been a marked increase in popular science literature on the aspects that make humans lie, if one goes by the sheer number of books on the subject. Yet it may well be that the issue has a totally different perspective that warrants further study and analysis: the idea that people suffer from an innate need to be fooled.

Magicians call this “a suspended state of wilful disbelief” — a state of mind where the spectator stops asking questions to the how and why of an illusion, and wilfully sets aside all critical abilities. If not for this state of mind, the audience would not be able to enjoy magic the way it is supposed to be.

The same goes for cinema or theatre. We put aside all our knowledge that this is make-believe and scripted, and immerse ourselves deep inside the story and live it in the moment-for real. Sadly, this need to be fooled looks to have now gone beyond the four walls of theatre and become a part of our lives. The need to be fooled is what drives most of our beliefs beyond the realms of what is logical and scientific. Then again, all this is just a theory, as untested as the other tall claims.

I for one would love to know what the behavioural scientists think about this. Wouldn’t you?

(PS: Originally posted online on Aug 6, 2014 at Medium.com)